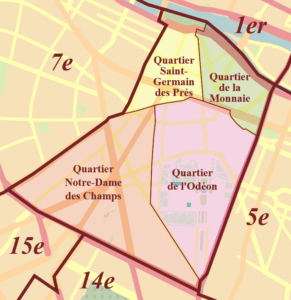

TODAY’S ARTICLE is a follow-up to my previous post which began an exploration of that most quintessential of all Left Bank districts; the Sixth Arrondissement. In this, and periodic posts to follow, we’ll take a closer look at the various neighborhoods of the 6th (there are four of them) and detail pieces of their history & culture that support my belief in this district as the essence of all that is wonderful about Left Bank Paris.

Of the four official quartiers within the 6th Arrondissement the neighborhood of St-Germain-des-Prés is the oldest and most famous. To appreciate the rest of the 6th requires a basic grasp of this original neighborhood. But with nearly 1500 years of history it’s a challenge to lay down its historical foundation while not losing the attention of the average reader whose interest usually covers only the last century or so. To entertain and inform without getting bogged down in the footnotes; a tough assignment considering the rich tapestry of events woven into every street and building.

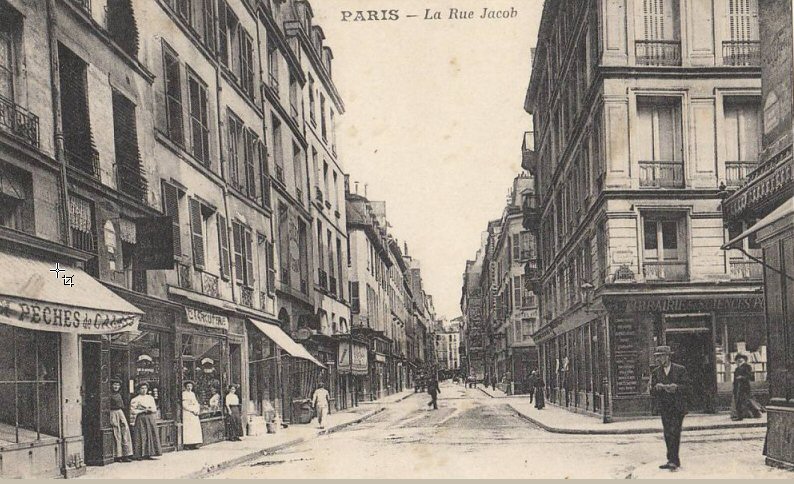

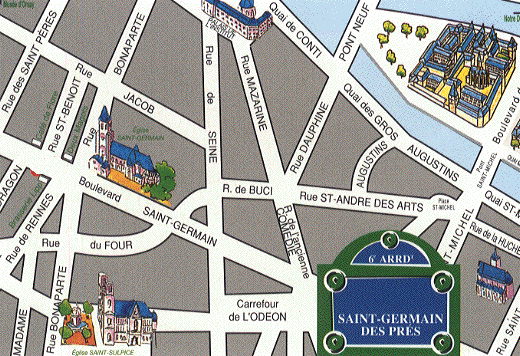

Fortunately, for those who know where to look, there are creases in the topography of the quarter that allow a glimpse of the historic strata in a relatively compressed space . One such seam is the neighborhood’s principal east-west street: Rue Jacob. A stroll along its short length provides a cross-section of the quarter’s rich history and allows us to take in the past and present of St-Germain, from the remnants of a once magnificent abbey, to the lodgings of great men and women in the arts and literature, to legendary cafes and contemporary jazz clubs, galleries and shops.

The Rue Jacob begins at its eastern end where it connects with the equally historic Rue de Seine. Rue de Seine traces a centuries old path that threaded its way to the river between the medieval walls of the city of Paris and the walled abbey of St-Germain-des-Prés. Today it is chockablock with small art galleries and intriguing interior courtyards.

Looking north and west from this corner one is enveloped in the classic Left Bank milieu of narrow streets, five story 17th & 18th-century buildings and, despite foot and motor traffic, a certain calm that simply doesn’t exist in most quarters of the city. The busy Buci/Seine street market is only a bock to the south but its bustle is baffled and absorbed as we turn into the ancient abbey precincts.

Heading west, we immediately cross the charming little street of Rue de l’Échaudé. This narrow lane marks the eastern boundary of the old abbey complex. For years I was intrigued and confused by its name. The word “échaudé” means “scalded” and I tried to imagine what sort of manufacturing or medieval torture might have conferred that name upon this street? I eventually learned that échaudé is also an old fashion pastry shaped like a triangle, and that in this instance it referred to a triangular block of houses that formerly existed along this lane. Voila ! Mystery solved.

A few more steps to the west and a left turn into Rue de Furstemburg brings us to one of the gems of St-Germain, the intimate Place de Furstemburg. This much painted and photographed bubble of serenity was originally the courtyard of the abbey’s stables. In the 19th Century the great Romantic painter, Eugène Delacroix, spent the last years of his life in a flat at No. 6. Today that studio is the Musée National Eugène Delacroix, an under-visited but worthwhile museum. Recent decades have seen the intersection of Rue Jacob & Rue de Furstemburg become a hub of upscale interior fabric and upholstery purveyors and their attractive window displays add a tony appearance to this part of the neighborhood. Most recently, the Parisian craze for niche patisseries finds expression in La Maison du Chou at #7, a shop devoted exclusively to cream puffs – yummy!

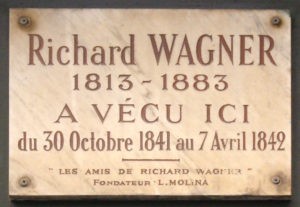

Back on Rue Jacob, the occasional wall plaque above a doorway reminds us of the host of notables who have resided here over the centuries. From artists & composers, to poets, politicians and exiled Hungarian patriots, the entire street is a Who’s Who of famous personages from the past four centuries.

At other addresses, signage has yet to catch up with history and most tourists pass by noteworthy buildings unaware of the stories their closed doors could tell.

At # 20, no plaque exists, although it certainly should, to recall this address as a vortex of literary life during the Lost Generation years of the 1920’s. For this was the home and literary salon of that maven of American Expats, Natalie Clifford Barney.

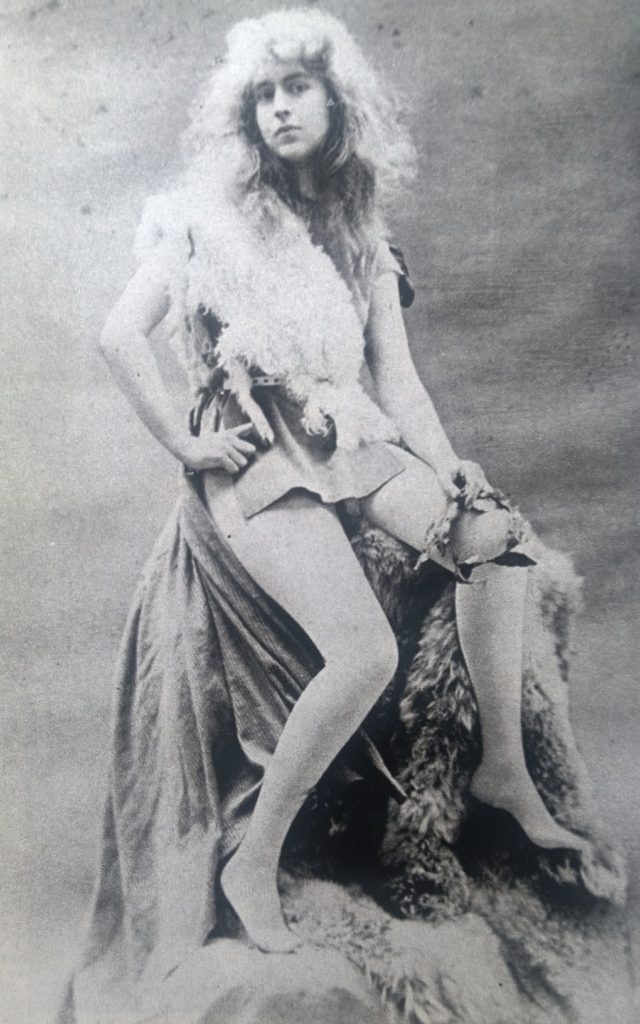

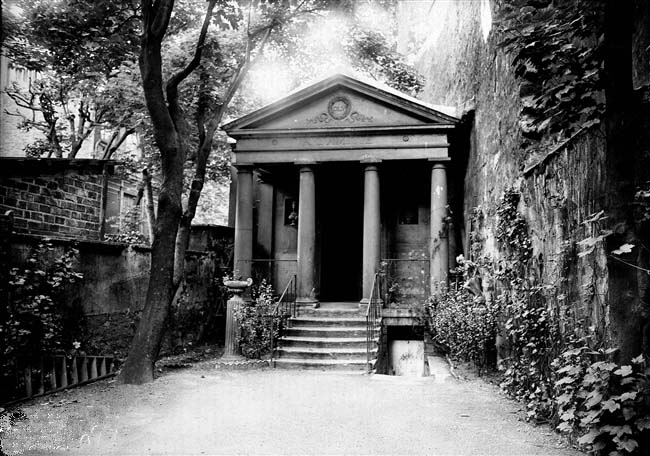

Intelligent, charismatic, fluent in French, and financially independent, Natalie Barney fled the puritanical constraints of late 19th-century Ohio, arriving in Paris in the early 1900’s. Her family’s wealth allowed her to pursue a career in writing and poetry, and to live a lifestyle beyond that of the struggling writers and artists who flocked to her salon after WWI. Behind the heavy double doors of # 20, a large courtyard contained a faux Greek Temple, dubbed the Temple de l’Amitié, where guests would cavort, often in Greek togas, sometimes naked. Tea was originally the beverage of choice at Natalie’s gatherings but the hard drinking expats who arrived in the 20’s introduced liquor to her Friday afternoon salons which further relaxed inhibitions in the Temple of Friendship.

Barney was openly and unabashedly lesbian and her life was a string of tempestuous female affairs. Her guest list contained all the names of 1920’s and 30’s expat Paris; Fitzgerald, Ezra Pound, Picasso, Djuna Barnes, Man Ray, T.S. Eliot and the list goes on. Interestingly, one name was frequently absent from her livre d’or; the other den mother of the Lost Generation set: Gertrude Stein – Stein preferred to hold court at her own salon near the Luxembourg Gardens on Rue de Fleurus.

While Rue Jacob is conspicuously lacking in cafes and dining establishments, it’s equally conspicuous for the large number of boutique hotels along its less-than-quarter-mile-length. At least eight 3 and 4 star Inns are to be found here, or just around the corner on its feeder streets. It was as a resident of one of those small bohemian hotels in the Summer of 1982 that I first became acquainted with Jacob’s street. In the intervening three and a half decades I have managed to stay at least once at every one of them. Over those years their quirky character has been upgraded with better plumbing, contemporary wallpaper and bedding, and slightly larger elevators. In short, they have become “yuppiefied”. The rates have increased in proportion to the gentrification but compared to rates across the city they are still a decent value.

While each hotel has its charms, there are a couple that stand out. For the bonafide Yuppie, the Hotel Millesime leads the pack. It is the sister hotel of the classy 5 star Hotel D’Aubusson, a few streets away on Rue Dauphine, and the management style, service, and high level of consistency at both are exemplary.

A few doors down, the Hotel des Marroniers is a sentimental favorite. Guests are drawn across its cute interior courtyard by the welcoming awning above the front door. A leafy garden patio in the rear is an island of calm in the heart of Paris where breakfast or afternoon tea may be enjoyed. Its rooms, though recently upgraded, still exhibit the diminutive dimensions and oddball floor plans that epitomize the Left Bank lodging experience. Bohemian and still a bit quirky, it is a residence for lovers; those in love with each other, and those in love with Paris.

Passing a few more boutique hotels and interior design shops, we arrive at the corner of Rue Bonaparte. This intersection is the compass rose of the quarter. To the north, the Seine and École des Beaux-Arts; a few blocks to the south, the entrance to the church of Saint-Germain-des-Prés and the legendary cafés of Les Deux Magots and Café de Flore; to the east and west, equal lengths of Rue Jacob.

Of the many landmarks and scenes of noteworthy occcurance that radiate from this corner, one of the most significant was the plot of land that once occupied much of this area: the Prés-Aux- Clercs.

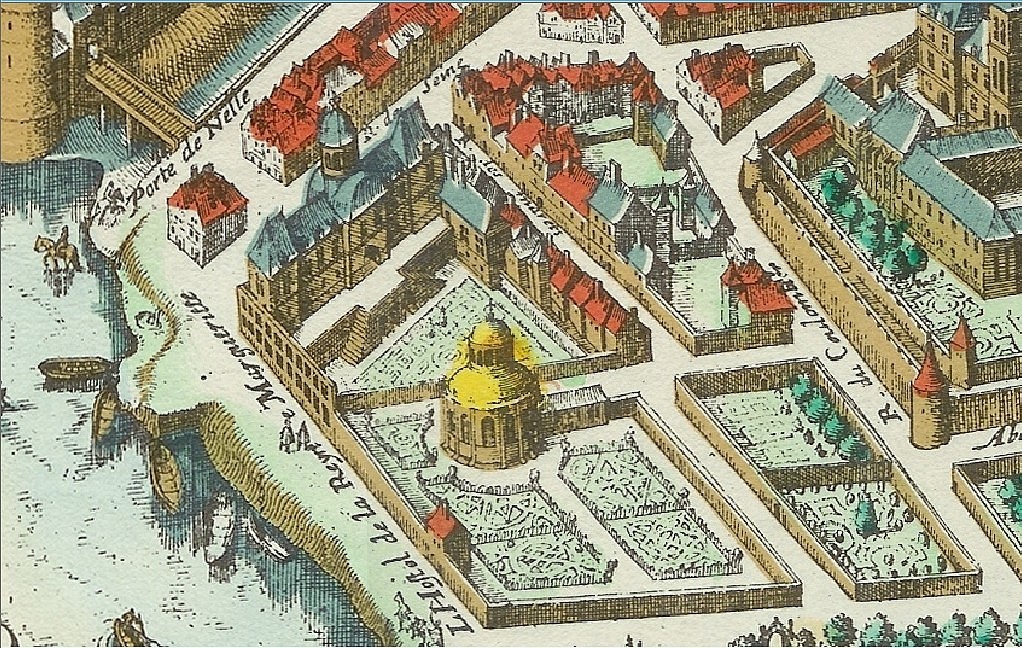

Medieval records are sketchy as to just how the University of Paris, subject to the Bishop of Paris, wrested the land between the abbey and the river from the Benedictine monks who were under the direct authority of the Pope, but from the Middle Ages it was a place of recreation and hijinks for the university’s students known as “Clercs”. It was also the occasional scene for duels of honor. At the beginning of the 1600’s, the eccentric former queen of Henri IV, Marguerite of Valois, took a large portion of this land for her sumptuous private mansion facing the Rue de Seine. The royal and ecclesiastical strings she pulled to acquire this acreage have been the topic of suspicious speculation. So much so that the riverside quay beside her palace took the name Quai Malaquais, derived from the words mal acquis (Wrongly acquired). She had large formal gardens laid out on the grounds to the west and won popular acclaim for opening those gardens the public. In the center of the garden, along the present day Rue Bonaparte, she had a chapel erected for the perpetual adoration of the Old Testament Patriarch Jacob, from whence Rue Jacob would eventually take its name.

Jacob’s chapel would later be incorporated into a larger convent church. During the French Revolution that church became the repository of artwork and statuary rescued from churches and palaces that were desecrated by the revolutionary mobs. In the 19th Century that collection became the nucleus of the École des Beaux-Arts (National School of Fine Arts) whose entrance still runs along the Rue Bonaparte.

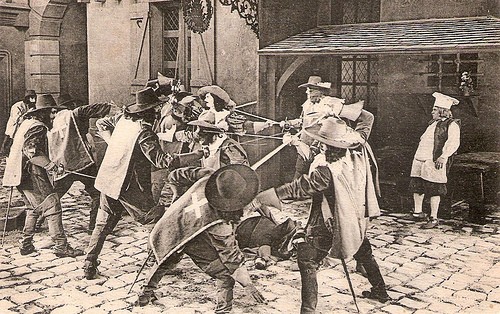

Later in the 19th Century the author of The Three Musketeers, Alexander Dumas père, would conger up recollections of the Prés-Aux-Clercs by making it the setting for the famous sword fight between the Musketeers and the Cardinal’s Guards.

Today, just about the only reminder of the Field of Clerics is the bistro on the southwest corner of Rue Jacob & Rue Bonaparte which bears the name Prés Aux Clercs. Few modern day patrons or passersby have any idea of the long association that name had with this neighborhood. While not noted for the quality of its cuisine this bistro is nonetheless a longtime neighborhood hangout and seems to have made an effort to take its game up a notch, if the recent renovation and expanded menu are any indication.

Continuing west on the last leg of our walk we pass by Rue St-Benoit on our left. This street marks the western boundary of the ancient abbey complex. Today it is a busy street of restaurants, boutique hotels and the famous Chez Papa jazz club, one of the few remaining jazz venues that the quarter was once renowned for.

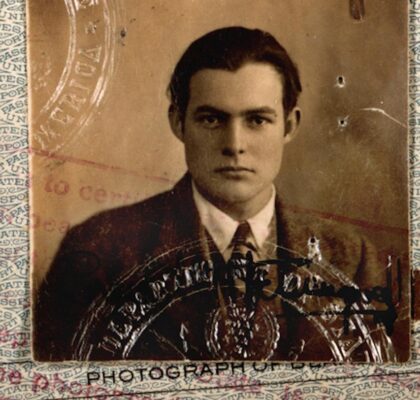

To our right, at # 44 Rue Jacob stands the Hotel D’Angleterre; a hostelry rich in history. On December 20. 1921, Ernest Hemingway and his bride, Hadley, arrived in Paris and checked into room 14 of this hotel, then known as Hotel Jacob & Angleterre. Other literary figures had preceded them; James Joyce, Sherwood Anderson, and decades earlier, Washington Irving. The Hemingway’s remained a few weeks until they found an apartment at 74 Rue du Cardinal Lemoine. Today, if you book far enough in advance, you may be able to reserve the “Hemingway Room”. But even if you don’t score that coup, the Hotel D’Angleterre is the quintessential St-Germain experience. The rooms vary in size and decor like most lodgings in the neighborhood, but the cozy atrium where one takes breakfast and the attentive service of the staff make up for any peculiarity in the sleeping rooms. Needless to say, the location simply cannot be beat.

Of greater note than it’s literary connections is the D’Angleterre’s role in the founding of the United States of America.

In the late 18th Century this building was the British Embassy; hence its present name “Angleterre”(England). France had been an active ally of the fledgling American colonies in their war of independence against Britain and when it came time to formally conclude peace negotiations with Mother England, it made sense to all parties to do so in Paris. After months of negotiations, the formal documents were ready to be signed on September 3rd, 1783. Representing the United States were John Adams, John Jay, and the longtime ambassador to France, Benjamin Franklin. Franklin’s inclusion would prove to be problematic for David Hartley, the British Ambassador.

Back in 1774, when he was the Colonial envoy to the British court, Franklin had been summoned to the Privy Council and forced to silently stand and endure a vehement hour long tongue lashing from several British Lords regarding the recent Boston Tea Party incident. This humiliating experience permanently turned Franklin from a hopeful proponent of reconciliation into a firm advocate of independence. It no doubt left him with a lasting personal animus for The British government as well.

So on that September morning, as Ambassador Hartley invited the American delegation to enter the embassy, the opportunity for a little personal revenge was too much for Franklin to pass up. Franklin pointed out that, by virtue of being an embassy, the building was technically on British soil and he was not willing to conclude a treaty that acknowledged the victory of the colonies on the soil of the losing side.

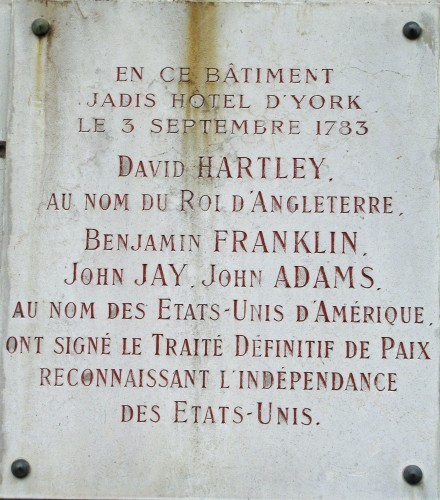

Embarrassed and bewildered, Hartley scrambled to come up with an alternative venue for the signing. He himself resided down the street in a townhouse called Hotel d’York, at what is now 56 Rue Jacob. So, with diplomatic egg on his face, he escorted the Americans a half block to that location to sign the treaty in his rented rooms. A wall plaque on the outside of that building commemorates the event.

It’s a fascinating bit of timeline trivia that the world’s 21st-century superpower had its official beginning on a 17th-century Parisian street paved over a filled-in 14th-century moat that surrounded a 9th-century abbey which encircled a 6th-century Frankish church built upon the foundations of a 2nd-century Roman temple dedicated to the 4,500 year old Egyptian Goddess Isis . . . The onion of history is peeled back quickly in the old quarters of great cities like Paris.

And what of Ambassador Hartley and his British cohorts? They showed their pique by refusing to sit for the official portrait commemorating the Treaty of Paris . . . Talk about sore losers !

Our tour of Rue Jacob ends a few steps farther west at the intersection of Rue des Saints-Pères. In the Middle Ages this street was a cow path that brought cattle from the river to graze in the western stretches of the Prés-Aux-Clercs. Today it marks the boundary between the the 6th and 7th Advertisements and is home to several high end antique shops, two very nice boutique hotels and the second oldest chocolate shop in the city, Debauve & Gallais.

On the other side of this intersection Rue Jacob’s name changes to Rue de l’Université; a reminder of the presence the University and its Prés-Aux-Clercs maintained in this area over the centuries.

The current café on the northeast corner was, in the 1920’s, the upscale restaurant, Michaud’s. When they could afford to splurge, the struggling artists and writers of the Lost Generation would be seen at Michaud’s. It was also the setting of the apocryphal incident, as recounted in A Moveable Feast, between Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald, in which Hemingway accompanied Fitzgerald to Michaud’s men’s room to evaluate his male member to confirm if it was sufficient to satisfy Scott’s wife, Zelda. Much to Fitzgerald’s relief, Hemingway judged it to be adequate.

IN CLOSING . . . With such a long history, so many events and so much human drama, it should not be surprising that Rue Jacob would also have a paranormal tale or two to tell. As a parting note, I’ll leave you with this witty, and only slightly eerie, audio monologue from Joan Juliet Buck, the former Editor in Chief of Paris Vogue magazine:

Click Here for “The Ghost of Rue Jacob”

BONUS:

Click Here: Archival video interview with NATALIE BARNEY in 1962, at the age of 90

4 thoughts on ““Exiled” in St-Germain, PART II”

Comments are closed.

Really enjoyed this history lesson (as history is not my forte) and look forward to reading much more. For some reason, I did not receive this or the previous post through my e-mail (although when I tried to subscribe, I was told my e-mail was already subscribed) and, luckily saw this on Facebook – so now I’m caught up. Thanks, Mike, as our strolls through the 6th will now mean a little more than in the past and I’m discovering there is so much more than just food.

Hi Susan,

I’ll double-check to insure you are included in future mailings.

If you liked this post and the one before it regarding St-Germain-des-Pres, I’d recommend you also red my post abut Ile-St-Louis; lots of good historical info about one of the city’s most romantic neighborhoods.

A bientot,

It seems that you are creating your own paranormal spirit in Paris. I know I feel it through these pages; a spirit of the Lost Generation …… Mike, we were born too late, I could see hanging with Hemingway or F. Scott much like my favorite movie of all time; 2011’s “Midnight in Paris”.

Right you are, Bill.

I often think I should have, or perhaps did, live in the Paris of the 1920’s

But Woody Allen’s classic film, Midnight in Paris teaches us that THIS is the best time to be alive and in Paris.