When conducting my walking tours of Paris I frequently remind my fellow strollers (flâneurs) to LOOK UP, as so much of the city’s architecture, historical signage and grand vistas are missed if people have eyes fixed on the sidewalk immediately before them. That notwithstanding, there are many instances when it does pay to peruse the sidewalk immediately below one’s feet to catch the many historical markers embedded in the pavement. Here are some of the more notable examples:

The Paris Prime Meridian

Anyone with an interest in geography or navigation knows that the Prime Meridian is the zero line of longitude and zero hour for world time zones. The modern day meridian passes through the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, England, hence the reference to “Greenwich Mean Time”. This official designation was not arrived at until 1884 via a convention of 25 nations. Prior to that, several points were considered for the designation, among them, The Great Pyramid of Giza, the Vatican, the Temple of Jerusalem and the Leaning Tower of Pisa. In the 17th Century the Sun King, Louis XIV, also claimed the designation for Paris. Louis, in his usual absolutist manner, proclaimed that a line running through the Royal Observatory in Paris should be the zero point from which all other worldwide measurements were calculated. For a time many maps and charts did indeed use this imaginary line for zero longitude. Eventually Greenwich, England won out but one can still see today where Louis XIV’s Meridian ran.

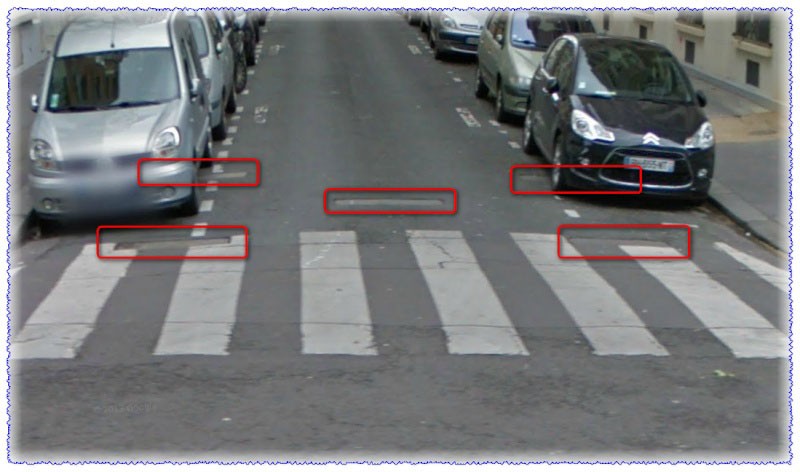

That’s because in 1994 the city of Paris commissioned a Dutch conceptual artist, Jan Dibbets, to create a memorial to the great French mathematician, physicist and astronomer, François Arago. Because of Arago’s work on, among many other things, the calculation of longitude, Dibbets came up with the idea of setting 135 bronze medallions into the ground along the old Paris meridian between the northern and southern limits of Paris: a total distance of 9.2 kilometers /5.7 miles. Each medallion is 5 inches in diameter and marked with the name ARAGO plus N and S pointers. Thus, a tribute to a 19th-century scientist has coincidentally provided the world with a reminder of this 17th-century meridian.

Many of the medallions are found in obscure side streets but there are several clearly visible in the Palais Royal and Louvre courtyard areas. When you come across one, plant one foot on either side of the marker and you will be astride the two ends of the Earth, as Louis XIV imagined it.

TRAVELER’S TIP: One of the ARAGO markers is located directly in front of Café Nemours on the Place Colette, between the Palais Royal and the Louvre. The terrace of Café Nemours is a very chic spot from which to watch Tout-Paris pass by. So much so, that it was the setting for the opening of the 2010 film, The Tourist, where we are introduced to a ravishing Angelina Jolie, dressed to the nines and taking her morning café. You would do well to do the same.

Address: 2 Place Colette

Click here for MAP

An End to Sexual Orientation Discrimination

Midway along the bustling pedestrian shopping street of Rue Montorgueil, at the corner of Rue Bachaumont, a plaque was set into the pavement in 2014. Attending the unveiling of that plaque were Paris mayor, Anne Hidalgo, local officials, and members of the Gay community. The ceremony was to commemorate the arrest of two gay men on that spot in 1750.

Jean Diot, a 40-year-old domestic worker, and Bruno Lenoir, a 20-year-old shoemaker, were arrested on Jan. 4, 1750, when police caught them engaging in consensual sex in public. Both men were imprisoned for six months, and after a trial in which prosecutors stated they wished to make a public example of the pair to discourage others from engaging in “criminal sodomy” they were executed on July 6, 1750, by being burned at the stake at the Place de Grève, now the Place de l’Hotel de Ville–the site of Paris’s City Hall.

Their executions marked the last time gay men or lesbians were sentenced to death in France due to their sexual orientation. In 1791, the nation’s penal code was revised to remove sodomy as criminal activity.

Click Here for MAP

TRAVELER’S TIP: Just a few yards from this plaque, on Rue Bachaumont you’ll find a charming retro bistro called Aux Crus de Bourgogne. In the same family since it opened in 1946, it retains an authentic 40’s – 50’s feel. It serves a traditional menu including some of the best Boeuf Bourguignon in the city.

Address: 3 Rue Bachaumont

The Death Of A King

One of the most notable and widely admired of all French kings was Henri IV who reigned from 1589 to 1610.

Henri’s life reads like a novel. Embroiled in France’s’ Wars of Religion, he converted from Protestant to Catholic to bring peace. An urban visionary, he did much to change the cityscape of Paris, including the building of the Pont Neuf and the Place des Vosges. A notorious lady’s man, he earned the nick name of “Le Vert Galant” (Old Charmer). But despite his popularity with many subjects, particularly the poor, he was equally hated by enemies both political and religious.

Henri successfully avoided at least 17 attempts on his life, but his luck ran out on the afternoon of May 14, 1610. Riding in an open carriage from the Louvre palace to an appointment at the Arsenal, his carriage was stalled in traffic on the ancient and narrow Rue de la Ferronnerie, near the present day Fountain of the Innocents. An unhinged Catholic fanatic, Jacques Ravaillac, had been trailing the king that day, waiting for the right moment. As the royal cortege waited for two carts to be moved out of the way, Ravaillac leapt onto the carriage and plunged a long kitchen knife two (Some say three) times into the king’s chest. The king’s aorta was severed and he died almost instantly.

And what became of Franꞔois Ravaillac, the most infamous French assassin? It is a gruesome and compelling story, one which I explain in detail on my walking tour of the Marais district. Suffice it to say here that after nearly two weeks of torture to extract a confession, he was dragged to Place de Grève in front of Hotel de Ville (City Hall), publicly mutilated, had molten lead and boiling oil poured into his open wounds, and was then drawn and quartered.

Today, the only indication of that tragic day in May, 1610 is a large grey plaque embedded in the pavement. There is no inscription to memorialize the event, only the personal coat-of-arms of Henri IV. Most of the hundreds, perhaps thousands, of locals and tourists who tread upon that plaque each day have no idea of its importance. But now, dear reader, you do.

Click Here for MAP

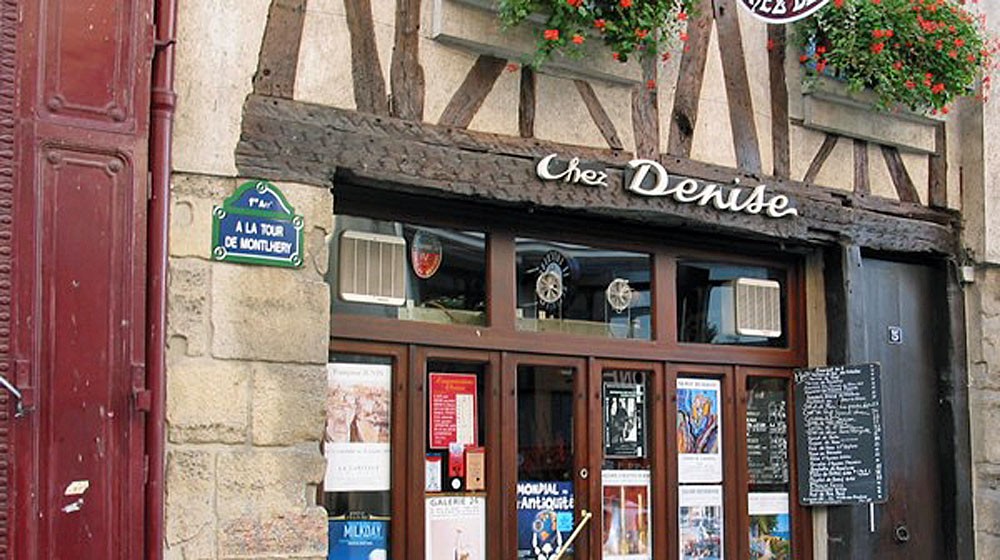

TRAVELER’S TIP: The Les Halles area is packed with eating and drinking establishments; most of them mediocre. But a scant 300 meters to the west of Henri IV’s plaque you can treat yourself to a stalwart old-school bistro, La Tour de Montlhéry – Chez Denise. Traditional cuisine in copious quantities has made Chez Denise a favorite for over seven decades. True to its origins as a café for all-night workers in the adjoining Les Halles produce market, it continues the tradition of late night service until 5:00 AM. Steak Tartare & Frites with a bottle of Brouilly at 4:00 in the morning . . . Mmm mmm.

Address: 5 Rue des Prouvaires.

SITE OF THE PARIS GUILLOTINE

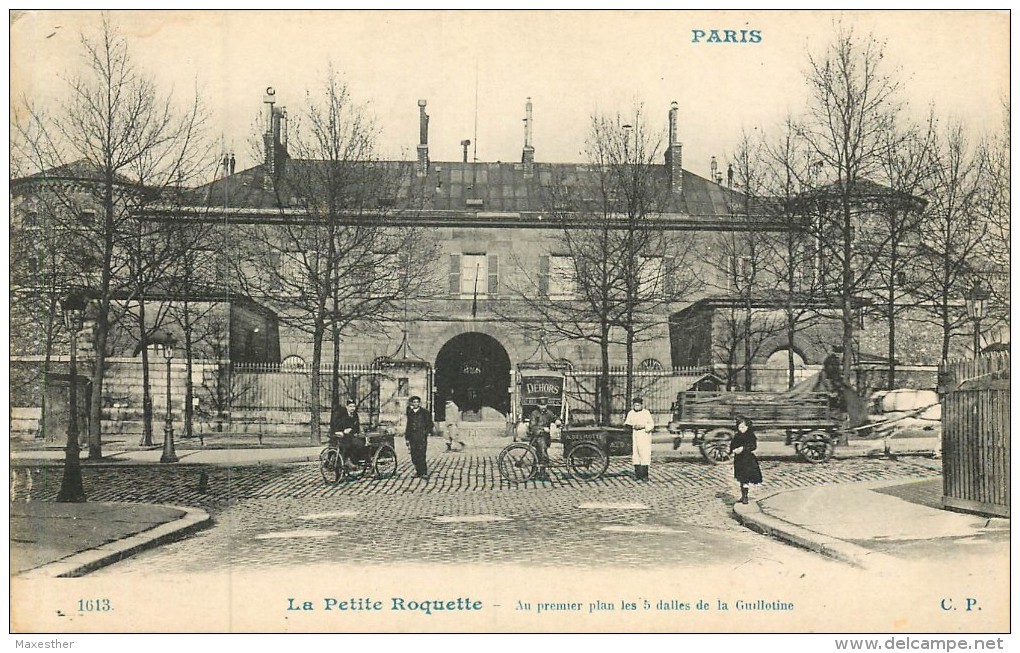

The Guillotine, that notorious device of execution made famous during the French Revolution, was the official form of execution in France for nearly two centuries. Long after King Louis XVI and his queen, Marie Antoinette, met their fate under the blade of Dr. Guillotin’s “Humane” machine in 1793, beheadings were still conducted throughout France, the last execution carried out as recently as 1977 in Marseilles.

In 19th-century Paris beheadings were public affairs, carried out immediately in front of the gates of the now demolished Prison of La Roquette, just a few blocks west of Pere Lachaise cemetery. The actual contraption was set up and dismantled for each execution, but for convenience, a set of five slabs (Dalles) were set level in the street, so that the guillotine could be easily set up on a level base each time. Though the prison is now long gone, replaced by a lovely park, the five slabs are still embedded in the street. Like many other pavement markers, passers-by walk ignorantly past them every day, unaware of the gruesome events conducted upon them.

Click Here for MAP

TRAVELERS’ TIP: A short walk south of the five dalles, the 11th arrondisement neighborhood of Rue Charonne provides a plethora of wonderful eating spots. One of the most charming is Le Pure Café. Good food, excellent coffee and a cozy milieu make it popular with tourists and locals alike.

Address: 14 Rue Jean-Macé

REMNANTS OF THE BASTILLE

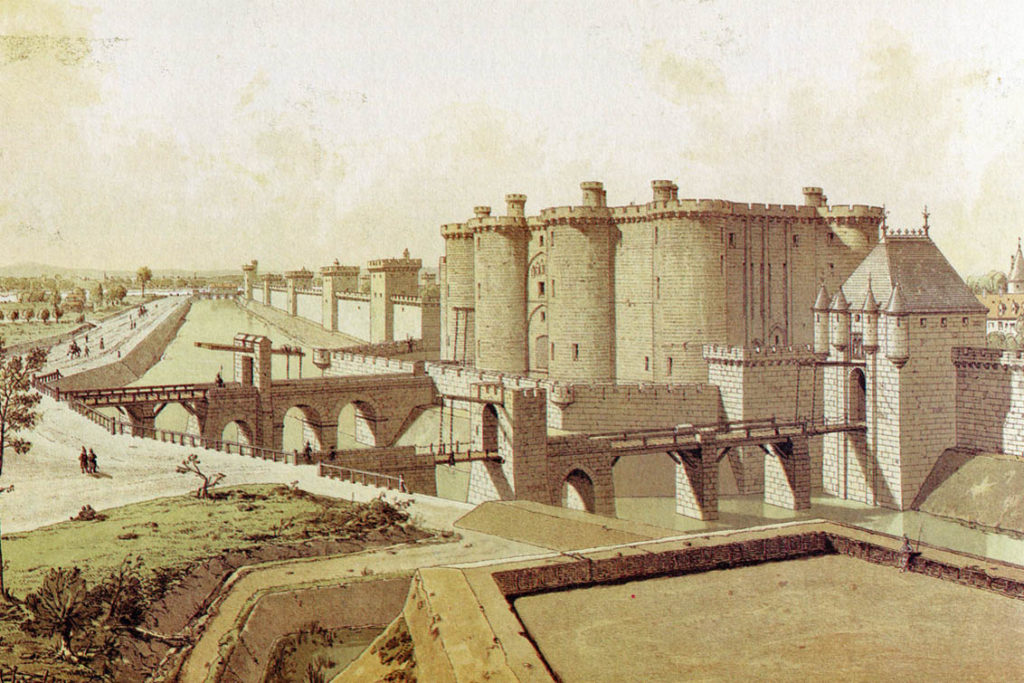

Synonymous with the French Revolution, the ancient fortress which guarded the eastern approach to the walled city of Paris looked out over what is now Place de la Bastille.

On July 14, 1789 it was stormed by a pre-revolutionary mob intent on freeing political prisoners held within. They succeeded in freeing a grand total of seven prisoners and murdering the warden of the prison; not a particularly auspicious start to a revolution. Yet history has passed down this as the blow that ignited the French Revolution and today July 14th is celebrated as “Bastille Day”; the equivalent of our American 4th of July.

Within days of the storming of the Bastille, the urban mobs began demolishing it as a rebuke of the royal tyranny they felt it represented. Bits of its stones were sold as souvenirs and a substantial amount was repurposed to build the Pont de la Concorde bridge, which still stands to this day.

Over the past two centuries so much urban renewal has taken place in the Bastille area that almost nothing remains to indicate the location of this important structure. But as you have probably guessed, there still exists a reminder in the pavement on the western side of Place de la Bastille.

Click Here for MAP

TRAVELERS’ TIP: Around the corner from the Bastille markers is BOFINGER, the oldest brasserie in Paris, dating from 1864. It serves traditional brasserie fare in a fin-de-siècle dining room, crowned with a beautiful Art Nouveau glass dome. (Make sure to peek into the men’s’ room downstairs for a look at the famous “Dolphin” urinals).

Address: 7 Rue de la Bastille.

A TREASURE TROVE IN FRONT OF NOTRE DAME

The centerpiece of Paris is NOT the Eiffel Tower, but the Gothic Cathedral of Notre Dame. This iconic structure occupies a prime position on the Île de la Cité, the island from whence the original settlement of Paris began over 2,000 years ago. Upon arriving at the Parvis (Square) in front of the church, today’s visitor is instantly drawn to the massive façade of the structure, eyes glued on the imposing building, often unaware of the important vestiges of Paris’s past that are literally right beneath one’s feet.

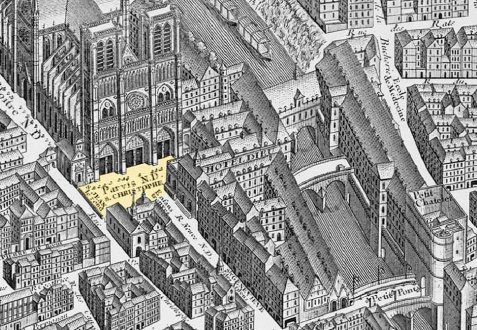

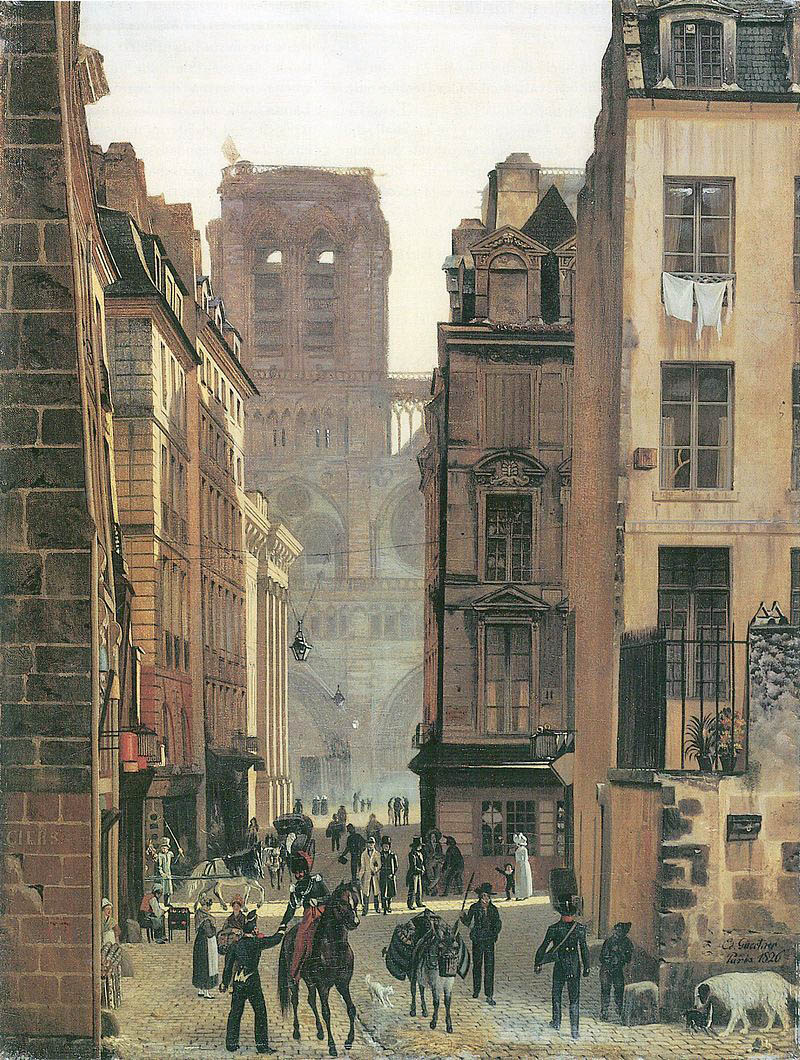

The church’s dominating aspect across the broad open square is a rather recent development. Until the mid-19th century the neighborhood surrounding the cathedral was a warren of narrow streets and alleys, medieval hovels and dilapidated houses. Several churches, chapels and convents, along with the ancient Hotel Dieu (hospital) also vied for space on the crowded island. The Parvis square in those days was only 1/6th its present size.

When construction of the cathedral began in 1163 a new street was opened through the quarter to connect the church to the royal court and palace at the western side of the island. The name of this street: Rue-Neuve-Notre-Dame (New Notre Dame Street). Along its southern side ran the large Hotel Dieu (Hospital). On its northern side were, among other structures, the Chapel of St. Genevieve des Ardents and the Hôpital des Enfants-Trouvés (Foundling Home).

No other section of the city was as dramatically impacted by the 19th-century modernization program of Baron Haussmann as the Île de la Cité. Whole blocks of medieval dwellings were demolished, the Hotel Dieu Hospital was moved from the south side of the Parvis to the north side and the Rue Neuve-Notre-Dame was obliterated along with the chapels and foundling home beside it.

But the modern day visitor can get a sense of the crowded medieval streets of old Paris by taking note of the large light colored paving stones that run toward the Cathedral. These pavers trace the outline of the medieval Rue Neuve-Notre-Dame, as well as the footprint of the Chapel of St. Genevieve des Ardents. This chapel commemorated one of the many miracles attributed to Genevieve, patron saint of Paris. In 1130 a plague of ergot poisoning swept through Paris, killing 14,000 inhabitants in short order. Desperate to abate the scourge, the Bishop of Paris had St Genevieve’s casket carried to the steps of the old cathedral to 103 stricken Parisians waiting on the Parvis before the church. 100 brushed against the holy relic and, according to legend, were instantly healed. The remaining three were obstinate unbelievers and went away unhealed.

These pavers are the visible vestiges of the long history of the cathedral square. What is not immediately visible, but is literally right beneath one’s feet is the archeological crypt of Ȋle de la Cité (Crypte archéologique de l’Ȋle de la Cité). During excavation in the mid 1960’s for an underground parking structure beneath the square, an archeological treasure trove was unearthed; 2000 years of strata, including Roman walls, medieval foundations and 19th-century sewers. After 10 years of digging and research, the excavation was turned into an on-site museum in 1980, allowing visitors to glimpse layer upon layer of civilization and urban life from the pre-Roman Celtic Parisii tribe to the 19th-century world of Belle Époque Paris.

POINT ZERO

We’ll conclude with one more marker. This one is also embedded in the pavement of the Parvis of Notre Dame, about 50 meters in front of the cathedral’s central portal.

It is a bronze compass star surrounded by stones inscribed with the words, POINT ZERO DES ROUTES DE FRANCE (Point Zero of the routes of France). It is from this marker that all French cities measure their distance from Paris.

This spot, though not the geographical center of France, is certainly its spiritual and historical epicenter. A Roman temple existed here, most certainly built on the site of an earlier Celtic altar. The first christian cathedral of St Etienne occupied the Roman site, Notre Dame replaced St Etienne, and so on, and so on. Medieval passion plays were performed on the Parvis and A Te Deum of thanks was celebrated here in August of 1944, following the Liberation of Paris from Nazi occupation.

The current marker was installed in 1924 on the former site of the Échelle de Justice, the gallows of the Archdiocese of Paris; making it truly a site of the sacred and profane.

Thousands stand on the bronze star daily for a photo, most without any idea that they are standing at the vortex of French history.

Click Here for MAP

Traveler’s Tip: With all the monumental structures on the island, it is perhaps not surprising that there are relatively few dining places, especially at the island’s eastern end. Fortunately there is a neighborhood place, blessedly underdiscoverd, only a block or two from Notre Dame. Au Bougnat (The Coalman) is a throwback to the charming era of conviviality, good food and moderate prices.

Address: 26 Rue Chanoinesse